Sunday, January 25, 2015

Chasing Unicorns

The depths of winter, for a surfer in high latitudes, can be like an enormous game of meteorological hide and seek. Rainbows abound, but the proverbial pot of gold is always retreating over the brow of the next hill. Swells are often raw and powerful, generated by storm systems that follow closely behind and move over the coast bringing strong winds that swing on a dime. The clock is there to race as daylight hours are limited and large tides can cause good sand banks and reefs to turn on and off within an hour. It's all too easy to spend hours on end driving country lanes and slip-sliding down muddy tracks to check obscure little coves only to find out that you've missed the best of it someplace else. It can feel like you're spending all of your precious free time chasing unicorns - you know that you'll never get one, but it's worth it just to catch a glimpse every now and then.

Sunday, January 11, 2015

An Axe To Grind

At the risk of being labelled some sort of lumbersexual, I am going to share with you one of my most recently completed winter projects: the restoration of a vintage forest axe.

Whilst it could definitely be viewed as being a bit "bandwagon", this was a fairly urgent project for me as I split kindling on an almost daily basis throughout the winter months. Yup, it's not for hanging on a wall but for facilitating the fire that heats our home. I own a beautiful felling axe (given as a gift) but it is enormous and designed to do exactly as its name implies: fell trees. I can split large logs with this but any attempt to knock down kindling is an exercise in risking my fingers, so I needed a smaller axe. My options were to buy a cheap hatchet from the hardware store (crude, unrefined and often with an ugly hi-vis orange plastic handle) or pick up an old axe from a second-hand store and restore it. I chose the second option. Here's how it went down:

I struck gold early on and found these two dilapidated old axes at a house clearance store. I paid £6 for the two of them, which is cheaper than one new axe. I decided to restore the top one first as the red axe below it was sharper and could be used cautiously whilst I worked on its big brother. Step one is to get rid of the helve (handle) by cutting it off just below the axe head, removing the metal wedge if there is one and then drilling out some of the wood and knocking the helve out of the eye of the head. On some axes the head will practically fall off the helve, whilst others might be stuck tight.

Take the rusty, tarnished old axe head and place it in a vinegar bath overnight. Use distilled malt vinegar (the clear stuff) that you can buy from most supermarkets for about £1 and place it in a container with a lid so that the head is just covered. Put the lid on so that it doesn't make the room smell, and leave it for 12-24 hours so that the acetic acid can break down the oxidisation.

That done, put on some rubber gloves and use your thumb or fingers to rub the rust off the axe head. You might want or need to give the axe a light sand with 120 grit abrasive paper and put it back in the vinegar for another few hours to get the best results. My vinegar bath revealed a maker's mark - it was forged by A Morris and Sons of Dunsford, Devon. They've been making billhooks, slashers and edge tools since the 1800s and continue to do so, and have obviously produced axes in the past.

It will also reveal the hamon line along the bit - the line of distinction between the (darker) hardened steel of the bit and the (lighter) softer backing steel of the ret of the axe head. As you can see in the image above, the hamon line on my axe tapers off towards the bottom (the toe) which suggests that at some point the bit has been re-shaped.

Gather together the following things and if you don't have a workbench then commandeer the corner of a table (preferably outside): A clamp, a scrap of leather, a flat bastard-cut or second-cut file, various grades of abrasive paper (120, 240 and upwards), wire wool and a sharpening stone. Clamp the axe head to your work surface, using the leather to both hold and protect it. Use the file and then ascending grades of abrasive paper and wire wool to clean up the main body of the head, always working in the same direction to remove scratches. Don't worry about going anywhere near the "sharp" bit. Your head may have a load of marks that you can't reasonably remove - these are known as "history marks" and, unless you want to erase the character of your axe then you're best to just leave them be. It's best to complete this stage the laborious way, by hand, as using power tools (in particular a grinder) can heat up the axe head and damage the temper of the axe.

The next step is to make your shiny axe a sharp axe. Wear a thick work or gardening glove when you do this stage as your sharpening tool and therefore the fingers holding it are moving towards the sharp edge - and you want to keep them intact and on the ends of your hands.

Because my bit was good and blunt, with a few nicks and chips taken out of it, I had a fair bit of work to do to sharpen it. All of the sharpening strokes taken go into the blade, rather than down the length of it. Hold the file with a hand at either end (to guide it) and push the file into the bit, rounding out the top of the stroke as you come towards the end of the file. As you restore the sharp edge, you can move onto a sharpening stone or diamond file if you have one. Sharpening an axe will take time and patience as the part that you are trying to remove material from (to get an edge) is hardened steel. It should end up looking polished as one part is starting to in the image below.

You will need to sharpen both sides of the bit equally, and keep checking it as when you sharpen one side you cause a burr of material on the other. You may also leave dull spots (called candles) on the very tip of the axe. Keep checking and continue sharpening to remove them.

For final sharpening I cheated a bit and asked a friend to finish my axe head off on a powered whetstone sharpening/honing machine at his work. If you have this luxury then it will certainly ensure that you achieve a sharper axe a bit faster.

Once you've restored the head of the axe to something like it's former glory, you need to hang it (put a helve/handle on). You'll need a new handle, a hardwood wedge to fit, possibly a metal wedge, a mallet, coping saw and 120 grit abrasive paper. New handles, made from hickory for it's positive properties of shock absorbency and strength) are available at a lot of hardware stores, but often they are just as ugly as the ones on the axes that they sell (and I chose not to buy). You might need to shop around a bit to find one with nice straight grain that is the right length. Generally speaking, the larger the axe head, the larger (longer) the helve. I found a 16' helve which looked about right for my axe head. I took the head into the store with me so that I could check that it would fit.

To hang the axe, first push the helve as far into the eye of the axe head as it will go, which probably won't be very far. Holding the end of the helve so that the head is hanging down, give it a couple of whacks with a mallet. You'd expect this impact to cause the axe head to fall off the end of the helve onto the floor (you'd be forgiven for wearing a tough pair of boots), but what it actually does is push the helve further into the eye. Then remove the head (a couple of taps on the bottom of the head and a bit of wiggling should do it) and look at where there are marks or shaved areas left by the head. Use a file, electric sander or sanding block to remove material from these tight spots, and try again. Keep repeating this process until the head of the axe sits tightly low enough on the helve.

If you end up with a fair bit of the helve protruding above the head of the axe, then trim it down to about half an inch (15mm). Take your hardwood wedge and, with a little bit of glue applied to the leading edge to ensure that it holds, drive it into the kerf slot in the top of the helve. You want it to go as deep as possible so err on the side of a thinner wedge, whittling yours down if necessary.

Most axes also have a secondary metal wedge driven in perpendicular to the first hardwood wedge. I rescued the metal wedge from the old helve and carefully drove that in too. Be careful not to split the helve, though, after all that work. File and sand down the top so that it all looks neat and tidy, and give the handle a rub down with some 120 and 300 so that it's nice and smooth. I also drilled and countersunk a hole down at the bottom of my helve so that I have the option of hanging the axe up. The final stage is to oil the axe head and helve to protect them from corrosion and to provide a nice surface finish. Linseed oil is probably the most commonly used and readily available, and can be used on both the steel and wooden elements of your axe to protect it. Wearing gloves, apply some using a clean rag and being sure to apply extra to the end grain at either end of the helve as these will soak up a bit more. Leave the axe hanging for 24 hours, then wipe off any excess with a clean rag. If you have the patience to give it a light sanding and apply a second coat, that would be best. If you want to paint the helve to make it look more expensive than it really is, then do so before you oil it.

Once that's all done, you're ready to use it and start splitting kindling. Watch your fingers, mind, and don't be too precious about your new axe - it's a tool with a purpose, after all.

For more information on restoring and using axes, check out Best Made Co.'s blog series on the subject and the great resources on the US Forest Services website.

Monday, January 5, 2015

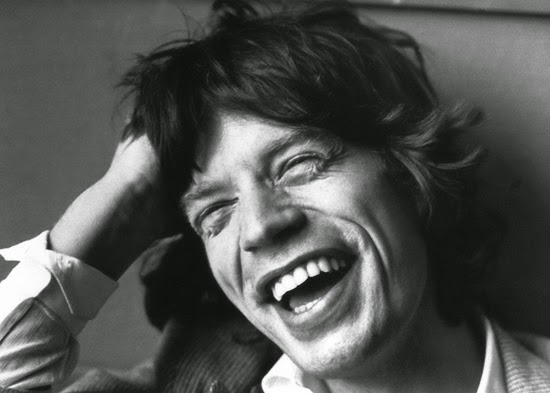

A Glimpse Through The Lens: Jane Bown

Jane Hope Bown, photographer,

13th March 1925 - 21st December 2014

Jane Bown was a staff photographer at the Observer newspaper for over fifty years, from 1949 until shortly just before her death last month at the age of 89. She was a legendary photographer who produced a large and consistent body of imagery over her career, working on 35mm film and almost exclusively in black and white until the end of her career. She was famous for using only natural light, favouring indirect sunlight from a north facing window to allow her to shoot at her preferred setting of f2.8 at 1/60 second. If she expected the light to be bad then, rather than use flash, she would set out (usually on the bus) to an assignment with the Observer picture editor's anglepoise desk lamp in hand. Bown was known to be uninterested in her equipment - she bought all of her cameras second hand and carried them in a wicker basket, and ignored the cameras inbuilt light-meter in favour of judging how the light fell on the back of her outstretched hand.

She had the unique ability when shooting portraits of the famous to produce iconic images from informal settings, putting her subject at ease and often completing the shoot within ten minutes or capturing portraits whilst they were being interviewed. These candid moments featuring some of the most iconic faces of the last 65 years were donated to the Guardian (the parent company of the Observer) and stand as a record of modern British popular culture over that period.

Camera-shy playwright Samuel Beckett - the third of five frames shot when Bown politely cornered him outside the stage door of a theatre.

Dennis Hopper

Queen Elizabeth II

Sir John Betjeman photographed, by the looks of things, near Daymer Bay in Cornwall.

Bjork

Michael Caine

Mick Jagger, mid-interview.

Richard Nixon

Tony Benn

All images copyright Jane Bown/the Guardian

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)